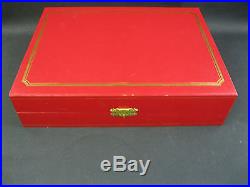

Up for sale I have this full set of crystals from my home country Portugal. This has been in our family for over 25 years and never used with original boxes and consists of 97 pieces. Please ask all you need or contact me at 9173186489. Glittering Crystal from Portugal. LIKE some ancient ritual fire dance, shadowy figures dart hither and yon, bearing blazing torches. One man jabs the air with a great glob of fire; another rolls a flaming mass in rapid swirls; still others breathe life into their burning bubbles. This carefully executed choreography is part of the traditional process for achieving some of the world’s finest handmade lead crystal. Visitors are welcome to witness this working ballet at the Stephens Factory School in the Portuguese coastal town of Marinha Grande, 80 miles north of Lisbon. Lead crystal, as its fans know, is glass with soul. It sings and dances and reflects a myriad of lights and colors. While artisans have for thousands of years been making glass by applying intense heat to sand, the art of making lead crystal is relatively new. Its discovery is generally attributed to an Englishman, George Ravenscroft, who late in the 17th century is said to have introduced lead oxide to the raw materials for glass. The result was as brilliant as rock cystal, with greater transparency, weight and sonority than other forms of glass; it was baptized lead crystal. The art of lead crystal has been perfected in several countries, and today the names of Bohemian crystal, Baccarat and Waterford have become internationally known. From Portugal, two great houses of crystal have acquired international reknown: Crisal, which is known abroad under the name of Atlantis, and Stephens. Stephens crystal has a long and colorful history. Two brothers from England, William and John Stephens, were said to have made a fortune from their limestone business in Lisbon after the earthquake of 1755. As the government was deeply in debt to the Stephens brothers, the ruling Marquis de Pombal gave them a small glass factory at Marinha Grande and an unlimited supply of firewood from the pine forest nearby. The Stephens brought in master craftsmen from England and Genoa and they introduced the idea of a factory school, giving the workers courses in letters, design and music as well as sports and cultural activities. The Stephens brothers left their factory to the Portuguese Government. The factory produced crystal services for government institutions and occasional prestige pieces but the bulk of the production was quality glassware. After Portugal’s bloodless revolution in 1974, factory discipline declined and production dropped until the government reasserted control two years ago. Under a new management team, the company has increased its crystal output, which now accounts for nearly 70 percent of the 1987 production of 370 tons.’This is a cultural institution more than a commercial enterprise,” Vitor Carvalho, president of the board of Stephens said recently, expressing pride in the exceptional skill and know-how of the company’s craftsmen. He showed visitors around the factory school, where 80 young people, starting at the age of 14, are enrolled in the crystal-making course, and another 80 are learning quality control; all are assured of employment in the factory. Well-known Portuguese artists have also been invited to work at Stephens, as the factory moves from traditional to contemporary designs. Among these is the sculptor Joao Cutileiro, who recently produced a crystal caryatid. Dorita Castelo Branco brought out a crystal commemorative medal this year for the European Year of the Environment. Major construction works are underway at the factory school, a group of handsome weathered yellow brick buildings, dating to 1769. The old Stephens’ residence, with its vast crystal chandeliers, sculpted plaster ceilings and blue and yellow tiles, is opening to the public this spring as a glass and crystal museum. The large brick dome, which in olden times was used to dry straw and has served as a storehouse, will be turned into a reception room for visitors. The old laboratory is to be converted into a showroom and the factory store expanded. In the factory itself, a new continuous gas furnace, with a capacity of 30 tons of molten crystal, was installed last year. English or Portuguese-speaking guides are on hand to explain the process of crystal making, which is similar to glass except that crystal is softer and easier to cut. Stephens crystal, we were told, is of superior grade, with 30 percent lead oxide, 3 percent density and 1,545 refraction index. The raw materials include silica imported from Belgium, potassium carbonate and potassium nitrate imported from Israel and Spain, lead oxide and sodium carbonate from Portugal. FROM a safe distance, we could see the genesis of a lead crystal goblet. First the red-orange powder is sent to the continuous tank furnace where it is melted at 2,786 degrees Fahrenheit and then slowly cooked to become homogenous. The compact molten mass was dropped from a platinum tube into cylinders. A blower picked up a glob with a hollow pipe and reheated it in a small brick oven. Then he blew the first bubble, shaping it at the same time by rotating it in a wooden form. Next he intro-duced the bubble into a mold, continuously blowing and turning it to make the final shape. An assistant brought another small glob of crystal from the furnace and attached it to the bottom of the cup to make the stem. The blower rotated and pulled the mass into shape with metal pincers. Another burning glob was put in place and rotated to form the foot of the goblet. While one man held the goblet with tweezers, another hit the top with a wooden spatula to separate it from the blowpipe. Then it was placed on a metal chain belt in a baking oven. After a stabilization period of about two and a half hours, the goblet was ready for finishing and cutting. During our visit to the cutting room, some workers were sandblasting emblems on decanters for Sandeman Port wine. Other cutters were using diamond wheels to scrtch floral patterns on vases. An artist was painting a meticulous design on a tiny perfume flask. In the factory’s exhibit and sales gallery, there was a wide variety of articles priced considerably lower than their equivalent in Lisbon stores. A family concern, Crisal glassworks was founded in 1944 by Fernando Magalhaes in the town of Alcobaca, near Marinha Grande. Crisal started out producing chandeliers, then domestic glass and in 1972, it went into lead crystal. Today two gas furnaces in the Alcobaca factory and a new electric furnace at Casal da Areia nearby produce only lead crystal, with 75 percent of the production exported to 35 countries around the world.’We believe our product is as fine as Baccarat and our prices are more competitive,” Fernando Magalhaes, assistant export manager and grandson of the founder, said. He described in detail the quality control observed in producing Atlantis crystal. If the piece has the slightest defect – an unwanted bubble, bend, crack or uneven surface – it is broken. All the broken crystal, about 20 percent of the production, goes back into the raw material or is thrown out. Crisal’s factories are not open to visitors. A WIDE range of high-quality Atlantis crystal is found in glass and crystal stores, shopping centers and boutiques in the main hotels in the Lisbon area. The item “Full set of glittering Atlantis Crystal from Portugal” is in sale since Monday, June 06, 2016. This item is in the category “Pottery & Glass\Glass\Glassware\Contemporary Glass\Crystal”. The seller is “jackforalltrades” and is located in Flushing, New York. This item can’t be shipped, the buyer must pick up the item.